HISTORY OF WELDON SPRINGS

Foreword

Bringing these long-hidden and often little known facts out of their hiding places and onto the printed page is a rewarding task that leaves the writer and researcher with few regrets. The difficulty of coming up with some of this data assures one that without his efforts some of them would never have surfaced.

Nevertheless, I do have regrets which go beyond the obvious, if I'd only started six months earlier before Joe died, I could have asked him many things. At no moment can that one be coped with without a time machine.

It is that so many worthy acts and people have helped make the park what it is without one word of mention. The writer can only outline what they have worked out in detail.

If I try mentioning Lester Oakley who worked faithfully with the group from its start until his death, or Beth Lighthall, who left us reluctantly to move to Australia, or George Luscombe, whose efforts have yet to slacken, I have shortened the list by only three names.

To all of you, my thanks and apologies.

History of Weldon Springs

By John R. Dawson

The first Weldon Springs Chautauqua opened on August 6, 1901. Judge Lawrence Weldon was unable to attend to kick off the ceremonies. In his stead, Colonel Vespasian Warner took over the horn.

He was a most fortunate choice, for he spellbound the crowd with tales of herding sheep in his youth under those same trees and on the area which now is the present lakebed. Since this period of the colonel's life was in the late 1840s and early 1850's (the county was barely six years old), we are unlikely to find oral or written accounts going back any further.

However, our print goes back to August 6, 1897. The Clinton Weekly Public passed along a Pantagraph report that Judge Lawrence Weldon planned to put $3,000 in improvements on the Weldon Springs, noting that, "It would be a good location for a hotel, camping and is less than ¾ mile from Salt Creek, where good fishing can be had."

The following week the Public stirred the subject again, hoping that Weldon would be joined in his efforts by Jacob Ziegler, adjacent landowner and astute businessman. Shortly afterward, Ziegler joined in, not as a sole partner but as an active member of the Weldon Springs Company. Ziegler discovered the second of the twin springs, walled them up with stone and cement, and built the (then wooden) steps going up on either side.

The Public also noted that Champaign had its Chautauqua along the banks of a stagnant stream, yet people came and were benefited. They mentioned the formation of a lake for boating and bathing, and expressed a belief in the medicinal qualities of the spring's water.

The avalanche was rolling. A delegation visited the site on October 5. W.H. Wheeler had had the land surveyed and estimated that the cost of building the dam would not exceed $1,000. Judge Weldon would not lease the land to private parties, but he would do so to an enthusiastic and active company.

A mass meeting of citizens was called for October 8. Estimates were taking shape and firming up. The dam would be 425 feet long and impound a lake of 15 acres. Superintendent Bailey of the Illinois Central figured that 6,000 yards of dirt would have to be moved at the cost of $3.50 per carload, for a total of $1000 to $1200.

The state would stock the lake with fish, and Weldon seemed ready to let the land go on easy terms. Lincoln Weldon was in town, and while he said he was not authorized to make an offer, he mentioned a 20-25 year lease, extendable, at $4 per acre, taxes to be paid by the company. If a company was organized, both Lawrence and Lincoln would take stock.

The proposed lake would take in all the springs but two, which were believed to have medicinal qualities. Bottled samples of these were sent to University of Illinois chemists for analysis, and it was hoped that the results would be available for the October 11 meeting.

These results were not announced that Monday, nor were we able to locate them in later issues. The idea was mentioned occasionally over the next few years, but gradually echoed its way out of our consciousness.

We shouldn't let that miscue cloud our image of these founding fathers. They were men of vision, and one suggestion that surfaced in an early meeting was that a long-range goal for optimal area would be around 400 acres. Ninety-three years later (1990), the total acreage was 370 with another 75 in the hope chest.

Prodded by W.H. Wheeler, the Retail Merchants' Association was solidly behind the project, and circulated papers for citizens to subscribe.

A goal of 200 shares at $50 per share was set in mid-October, but it was not attained when the charter was issued December 10, 1897, with 150 shares at $50 per share, for a total capital of $7,500. The majority of these prominent citizens signed on with one share each, though there was a sprinkling of two, and Richard Snell, who with W.H. Wheeler had negotiated the contract with Judge Weldon, is listed with four. (see Stockholder list)

The sale of stock did continue, and in time reached the $10,000 mark. The Weldon Springs Foundation has a certificate of the Weldon Springs Company made out to H.G. Beatty, a prominent Clinton merchant, dated October 14, 1899, signed by L.H. Weldon, President and E.B. Mitchell, Secretary.

The purpose of the company, as stated in the charter was, "To operate and maintain a medicinal springs sanatorium and pleasure resort at the Weldon Springs, located at Clinton, DeWitt County, Illinois."

Of the seven applicants who signed for the charter, two strike a spark in those interested in the origin of place names — L.H. Weldon, and J.F. Deland. You will find neither of these surnames in today's telephone directory, but both are on an Illinois road map.

The 50-year lease with the Weldon family laid out the charges and rules of the game. The charge was to be $4 per acre each year for the first 15 years. Then the site would be appraised by three men — one selected by the company, one by Weldon or his representative, and one by the judge of the circuit court — to set the scale for the next ten years. Then it would be re-appraised in the same manner to set the scale for the final 25 years.

At least $1,000 per year must be spent on the dam, walks, driveways, bathhouses and other buildings, etc. No alcoholic beverages were to be allowed. Judge Weldon was to buy $500 of Company stock.

A major surprise in thumbing through the evidence is that there is no record that Judge Lawrence Weldon ever attended a Weldon Springs Chautauqua. He was scheduled to be on the platform at the first one in 1901, but was prevented from attending by his duties on the U.S. Court of Claims in Washington. In the three succeeding years, his presence would have been physically possible, but The Clinton Public, meticulous in this respect and an avid fan of the Judge, made no mention of it.

However, we must credit the Judge with the original idea, the framework of which held steady throughout the formative years under his strong but largely invisible hand. He also passed on his love of the Springs and the land and the people of DeWitt County to his only son, Lincoln.

Not distracted by a legal career as his father was, and spending a much larger share of his time in Illinois, Lincoln Weldon was very active in the Weldon Springs Company and in the Chautauqua Assembly, though he was never one to take bows from the speaker's platform.

When the dam burst during the flood in 1911, it was Lincoln who quietly dipped into his own pocket for $500 to cover the repairs in time to limit the damage to that year's Chautauqua. Nor can we forget that it was Lincoln Weldon who expanded the original forty acres to fifty when he bequeathed it to Clinton. In addition, we can only imagine the pressures and prospects of financial gain that he resisted to bring the Springs to our generation in the pristine condition that it was left to him. The Weldons left a worthy name to a noble work of nature.

The $3,000 of improvements rumored to be coming from Judge Weldon in the original story was swept aside by the rush of events. All through the latter part of 1897, each story warned that if the lake was to be in place for 1898, work would have to be started in early fall.

In fact, work did not begin until the following spring, and the dam was completed July 23, 1898. It was first frozen over in the exceptionally early winter on December 2 of that year.

The hitherto lake-less county took to its new waterworld with gusto. In midsummer 1900 [sic], a young lady was drowned in a boating accident. (see news article) In the July 12, 1901 issue of The Clinton Register, there was a notice of an upcoming "union" picnic of all the Sunday schools in Randolph Township (Heyworth) which mentioned the availability of rental boats, that the steam launch, Columbia, was making trips on the lake, and that there was a pavilion capable of holding 1,000 people.

These accoutrements were welcome additions, and pulled increasing numbers of people to the Springs. They do not however mark the social beginning of the spot. One has only to peruse through any local paper of pre-dam vintage to be amazed at the number of reunions, picnics and other get-togethers that convened on the spot before the lake was there. (for later articles, see 'Old Four Families' Reunion and Pioneer Families at Weldon Springs)

In early 1901, DeWitt Countians were learning to live with their lake. In late June, a young man's life was saved after he was thought to be past resuscitation. On July 14, Frank Nebel, boating with friends, was not so lucky; this young man did not revive. (see news article)

However, these were individual tragedies; the great bulk of the county's interested population were planning and preparing for the first ever Weldon Springs Chautauqua.

As Rev. S.C. Black said in the Clinton Register on the eve of the event, a brand-new Chautauqua, while having a number of obvious drawbacks compared to established ones, had a number of factors going for it. Prime among them, the big names of the circuit might have been to the established site too recently and too often to be drawing cards. In addition, on the other side of the coin, performers often had the older Chautauquas built into their budgets, but were prone to look at a new outlet as the bearer of a bonus or a raise.

Added to these factors, a very capable committee had been unusually active. A dozen of the most popular names on the circuit, headed by Eugene V. Debs, Mrs. Carrie Nation, Sam Jones, Col. George Bain and Col. L.F. Copeland, plus an array of readers, musicians and singers appeared on the agenda. Mrs. Nation was the only one unable to meet her obligation.

Season tickets for the ten days cost $1.50, single admissions were $0.25, teams — in those days it was not necessary to add (of Horses) — $0.10; children were admitted free.

The first day, a Friday, bore out Rev. Black's predictions. Gate receipts were $150, compared to Bloomington's $45 first day that year. This, coupled with the occupants of 125 tents, brought the first day's tally to about 1,000 persons of all ages.

The following day showed a predictable slump. Pawnee Bill (Maj. G. Wm. Lillie), competing from a tent in Clinton with his wild west show, hippodrome and Mexican bull fights, cut gate receipts to a still satisfying $100. Sunday the Chautauqua was back on track with gate receipts of $400 and a total crowd of 7,000 to 8,000 people. To accommodate such numbers with a 90' x 60' tent, three sessions per day were scheduled — morning, afternoon and evening.

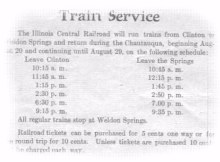

The Illinois Central Railway rose to the occasion with seven trains each way between Clinton and the park, plus an excursion train from Bloomington, which brought in 500 passengers on Sunday. Round trip fares to and from Clinton were $0.15.

At this distance, it would seem that the railroad was keeping its traces fairly taut, but for more than two decades rail service was high on the list of complaints and needed corrections were voiced each year when the assembly closed.

Cost was half the issue. The Record grumbled that a way must be found, "to deliver patrons for $0.10 per round trip without walking part of the way," adding that this was what accounted for the success of the Chautauquas in major cities. The last part of the quotation was the other half of the squawk, for unless one was sufficiently flush to hire the horse-drawn jitney service from the IC stop to the park boundary, that is exactly what happened. The half-mile-plus stroll may have softened the seats at the auditorium, but was not appreciated on a hot or rainy day.

In addition to improving the transportation, plans for the next year included building an auditorium (also not achieved), upping the number of tents from 125 to 200 (exceeded) and bridges over the west arms of the lake.

The bad luck that seemed to have the lake targeted earlier in the year zipped past with a couple of near misses during Chautauqua. On Wednesday, August 21, the two incidents happened within half an hour of each other.

One of the pair of two-year-old twins of the Rev. M.F. Ingraham of Wapella rolled down the bank and into the water. He was rescued by Harry Savidge of Farmer City and Milo Twist of Weldon as he came up the second time.

Half an hour later, as Fred Ziegler was gassing up the steamer, Columbia, an explosion and fire occurred that forced the two men on board to dive into the water, but neither was injured, and the fire was extinguished without any damage to the launch.

The weather problem the first year had been drought. The opening parade had been cancelled because of dust, and sprinklers were on the roads and grounds day and night through a large part of the Chautauqua.

In the second year, management and patrons battled the opposite extreme. The preceding weeks had been wet, and farmers were struggling to save their grain, notching into weekday crowds. On opening night, strong winds and rain knocked down the Big Tent and severely damaged many of the residential ones in White City, as the camping area was called. Many campers left for lack of tents. The wedge-shaped tents had leaked the least, and from then on were the most popular.

Nevertheless, they had started out with 250 tents that year so even with the defections tent population was up. In addition, with the return of good weather, more campers came in, for eventual 325 tents.

The Big Tent was re-hoisted undamaged. With dimensions of 128' x 68' it was capable of seating a crowd of 2,000, virtually doubling the first season's capacity.

The principal speaker of 1902 was Senator Tillman of South Carolina, who ably articulated the Southern viewpoint on the Civil War and Reconstruction. He was introduced by his friend and political antagonist, Representative or Congressman Warner, and the Colonel is never mentioned again.

Also in the political vein was a debate between Rep. Champ Clark, Democrat of Missouri. and Rep. Charles Landis, Republican of Indiana, on which party had caused the Panic of 1893, and whether we should hold on to the Philippines. At this point Clark was allowed an hour and a quarter; he finished in an hour, ten minutes. Landis, given fifteen minutes to reply, took thirty minutes to do so. Clark was back next year debating Charles H. Grosvenor. Landis disappeared from our roles.

The Illinois Central was still struggling with its mission. The schedule was beefed up, and 500 people came in on trains on Thursday night, one of the bumper ones. On the final Sunday, one excursion train came in from Havana and one from Deland. Still, there were complaints of service up to 20 minutes late and demands that the railway extends its track to the park boundary, or that a trolley be built.

Also realized was the need for more rowboats. However, complaints did not slow the sale of 1,268 season tickets for the next year and calls for the completion of an auditorium capable of seating at least 3,000 people.

Peak attendance (the last Sunday) was 8,000 of all categories — admissions, campers, and minors. Total receipts, $4,250, exceeded the first year by $550. Total costs were $2,000, several hundred more than a year earlier.

The year 1903 has come down in Weldon Springs Chautauqua annals as the year of the big tent flap. Headlines appeared in mid-July that 400 tents expected; bumper ticket sales assured it.

However, the Decatur firm which had the contract to supply the rental tents had overdone itself in getting maximum usage of its wares, and failed to notice a slight overlap of dates at Petersburg and Weldon Springs. Not only were 400 tents not available, but scarcely a respectable fraction of it. Tent company officials stonewalled valiantly, spoke of shipment to Clinton, Iowa, by mistake, placated, cajoled and hid until it was obvious to all that it was a dodge. A supplier in Springfield took over, and tent numbers swelled to equal the 325 totals had in 1902 . Also, in addition to the Big Tent that acted as an auditorium, there was the Headquarters tent, the Dining Hall tent, BarberShop tent and several refreshment tents. A contemporary account described it as 40 acres of water, tents, and teams. In addition, 1903 was the first year when increased acreage was seriously added to the Assembly's needs.

The teams were kept in semi-clear areas up near the entrance to the park. This was necessary because, as the crowds increased, there were virtually no tent-free areas in the park. In addition, at that time of year, shade was vital, but you couldn't have too many tree-trunks crowding out the horses. They were tethered as teams (better utilization of space) rather than loose and mixed in a corral.

Tent making in the early 1900's was a major business, as Chautauquas all over the country multiplied and expanded at a pace roughly comparable to that of Weldon Springs. There were also changes in designs and dimensions.

This resulted in minor friction along the lot borders — a 24' tent fits poorly into an 18' lot — that increased over the years. Minnie Twist of Weldon, a young lady who attended for several years with her parents and family, noted that it was an annual ritual. The tents were never ready when promised, crews had to be prodded, and the more accomplished naggers moved in ahead of the philosophical majority.

By 1914, residential tents were two and three times the capacity of earlier ones, and with the mix of old and new and different sizes, the number of tents had long since ceased to provide a reasonable tool for estimating the size of the crowd.

At first, four or five people per tent were a workably accurate guess. It doubled in the later models. To overcome the conflicts of overlapping lots, the lots were re-plotted to reflect the changes, generally possible by eliminating corner lots, which had been the ones most commonly left vacant.

Beginning in these early years and developing as it went along was a definite Chautauqua life style that all who attended remembered with nostalgia. There was a grocery on the grounds (at city rates), and ice, gasoline, bread and groceries could be delivered to your tent, unless you needed the chore to wear down the teenagers. In addition, several grocers in Clinton made two or more trips daily to the Springs.

There was a dining hall tent operated by the Ladies Aid societies of the various churches, and rotated yearly, where the food was inexpensive even by standards of those days. In addition, there was the ever-popular popcorn wagon.

Rounding out the list of available services were tents for the police (from the county sheriff's department), a post office, information center, a telephone station, a checkroom, physician's tent, feed yards, cabs and motion picture exhibitions.

The day before the Chautauqua opened, farmers converged on the grounds with a ten-day supply of camping necessities — a rug made of old carpets, cots and folding beds, oil burners with ovens, an old dresser, folding chairs and rockers.

To this list Anna Warren (now of Clinton, then of rural Farmer City), who attended several Chautauquas as a young girl, would not only add the ironing board but nominate it as the most essential. In addition to countering the wrinkle-producing propensities of ten outdoor days on the family wardrobe, it doubled as a dining and a buffet table, and a general storage counter to put things on. It was always in use in one capacity or another.

Refrigeration

being limited, there were live chickens staked out as each awaited his turn in the

pot; also, all kinds of fresh produce, eggs, hams and a large bowl of fresh butter

were on hand.

Refrigeration

being limited, there were live chickens staked out as each awaited his turn in the

pot; also, all kinds of fresh produce, eggs, hams and a large bowl of fresh butter

were on hand.

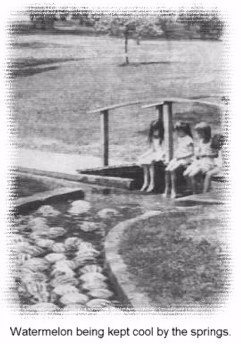

The less perishable items were carefully wrapped and covered and stored in the coolest corner of the tent, while those with the most urgent refrigeration needs were placed in the water chest which was submerged in the ditch running from the Springs. The fact that ice was mentioned as an available item at fairly early Chautauquas suggests that at least many families had some abbreviated or make-do form of a portable ice box, but the spring water was the most prominent and highly visible means of refrigeration.

Use of the natural refrigerator involved some risk on the night before the Chautauqua started (and there seems to have been some misappropriation) but once the water chest items had weathered that, the area was highly patrolled, and the only problem was finding an empty space. Crowds that size takes many water chests.

Shortly after the opening of the third Assembly, the park was hit by one of the heaviest rainstorms in years. Water rose several inches around the boathouse, with comparable amounts moving through the tents and belongings of the campers. However, the drainage was good and the patrons patient, and it did not distract for long from the good humor of the day.

More serious was the dilemma when William Jennings Bryan phoned from Chicago with the news that the death of an intimate friend would prevent his filling his contract as the principal speaker for opening day — and the entire Assembly for that matter. There was no ducking the issue. The crowd was in place, and there was no way of securing a comparable heavyweight. A.W. Hawks, the Laughing Philosopher and certainly the bravest man on the entire grounds, took over the rostrum adequately enough to prevent utter chaos.

Anyone tempted to wonder about the level of sophistication of a Chautauqua audience can go through the contemporary accounts and see how they rank with their grandchildren in the come and go of spending money to entertain and improve themselves.

As the Bryan incident shows they were less volatile than the patrons of some modern day rock concerts. They were also more tolerant of over-runs in the time allotment of a strong speaker.

Of course, they were trained in a more stringent school. Ministers of the day generally liked to hear a few snores to be certain that the alert majority were adequately saturated. In addition, politicians, a second major force in the Chautauqua movement, admired the sound of a profound or witty phrase as it rolled off their own tongues.

Senator Robert M. LaFollette, in 1907, had to cut his speech to two hours to rush for a train to get to Iowa to deliver his next speech. The final hour was filled in by an impersonator of LaFollette. Then, as now, there were many on stage, and handy as a clown in a rodeo. No one threw a fuss, although LaFollette was hailed by many as the greatest orator to ever speak at the Springs.

Chautauqua patrons could also understand bad luck and emergencies —as when Youna, a Japanese juggler, arrived to find his trunk and all his paraphernalia had been lost in a baggage mishap; they were as understanding as any group of today's airline passengers.

Nevertheless, they could let displeasure be known. One frontier character and Indian fighter had so pleased the audience the previous year that he was asked back, "But he didn't live up to expectations, and will not be back next year." On another occasion, a Rev. W.H. Crawford, lecturing on an Italian religious reformer of the 13th century, "Spoke brilliantly, but was not well received." On several other occasions when speakers failed to attain the expected level, they were, "Borne with patience."

Thus, there was no great break with the audiences today.

One short statement in The Clinton Record's sum-up of the 1903 Chautauqua was to cast a proportionately long shadow on Weldon Springs and the Chautauqua movement generally: "The Edison Projectorscope gave entertainment two nights." Again in 1905 we read, "American Vitagraph crowded the Auditorium showing moving pictures." Nothing further was mentioned on the subject until World War I when pictures from the Western Front were shown for a couple of years. But the genie was out of the jug.

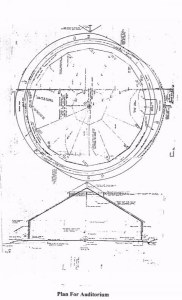

Weldon Springs officials were doing their best to maintain and enhance their offerings to the Chautauqua public. An auditorium, on the wants list from the start, had become necessary. Head-on competition with the World's Fair in St. Louis was in the offing, and the year-to-year growth of the crowds made even the largest of available tents woefully inadequate. The Auditorium, mostly of steel, 100' in diameter and capable of seating 5,000 people was the pride of the county for years.

The DeWitt County History (Pioneer, Chicago, 1910) tells us that the Auditorium was, "Built in 1904." This is not inaccurate (completed would have been a better word) but it led many of us to the inaccurate conclusion — built in 1904, in service in 1905. In fact, it was in service on the first day of the 1904 Chautauqua. It had its first capacity crowd a couple of days later the Champ Clark — Charles Grosvenor debate.

We know that the 1903 Assembly was conducted in its entirety in the Big Tent, so we can assume that the groundbreaking for the permanent structure occurred some time after the closing concert of that year.

We also have the statement of the Weldon Springs Company official that they had spent $15,000 on the grounds in 1903, indicating that a substantial part of the $5,000 cost had changed hands during the various stages of construction in that year, leaving only the completion hold-back for 1904.

A closely parallel matter in 1904 was the incorporation of the Weldon Springs Chautauqua Assembly with a capital stock of $3,000, divided into 60 shares at a par value of $50 per share. Its purpose, as stated in the charter was, "For social intercourse — the intellectual and moral elevation of the adjacent people."

Actually, it had been organized in 1901 and participated in obtaining and accommodating talent through all the Chautauquas at Weldon Springs, but its existence was not fully formalized until 1904.

Whether this was a move prompted by the unusual financial outlays of 1903 and the need to get new money into the coffers or an organizational gambit to keep the housekeeping chores separate from the talent searches will not be completely known until we find the financial records of one or both organizations.

The Weldon Springs Company had finished off the 19th century with its original $10,000 minus the costs of the lake, trails, pavilion, bathhouse, boats, etc. By the time the Chautauqua Assembly was capitalized, there was nearly six years' interest on the unspent balance, plus the surplus of three successful Chautauquas. The thumping outlays of the auditorium year would have left the account still sturdy but chipped down, and the new $3,000 may have nearly doubled it.

Reprinted with permission dated 2 Sep. 2002

Submitted by Calvin Keli Lunny